Eating California: A Living Portrait of Indigenous Foodways

Original Artwork by Alrie Middlebrook, article by Sophie Chertok

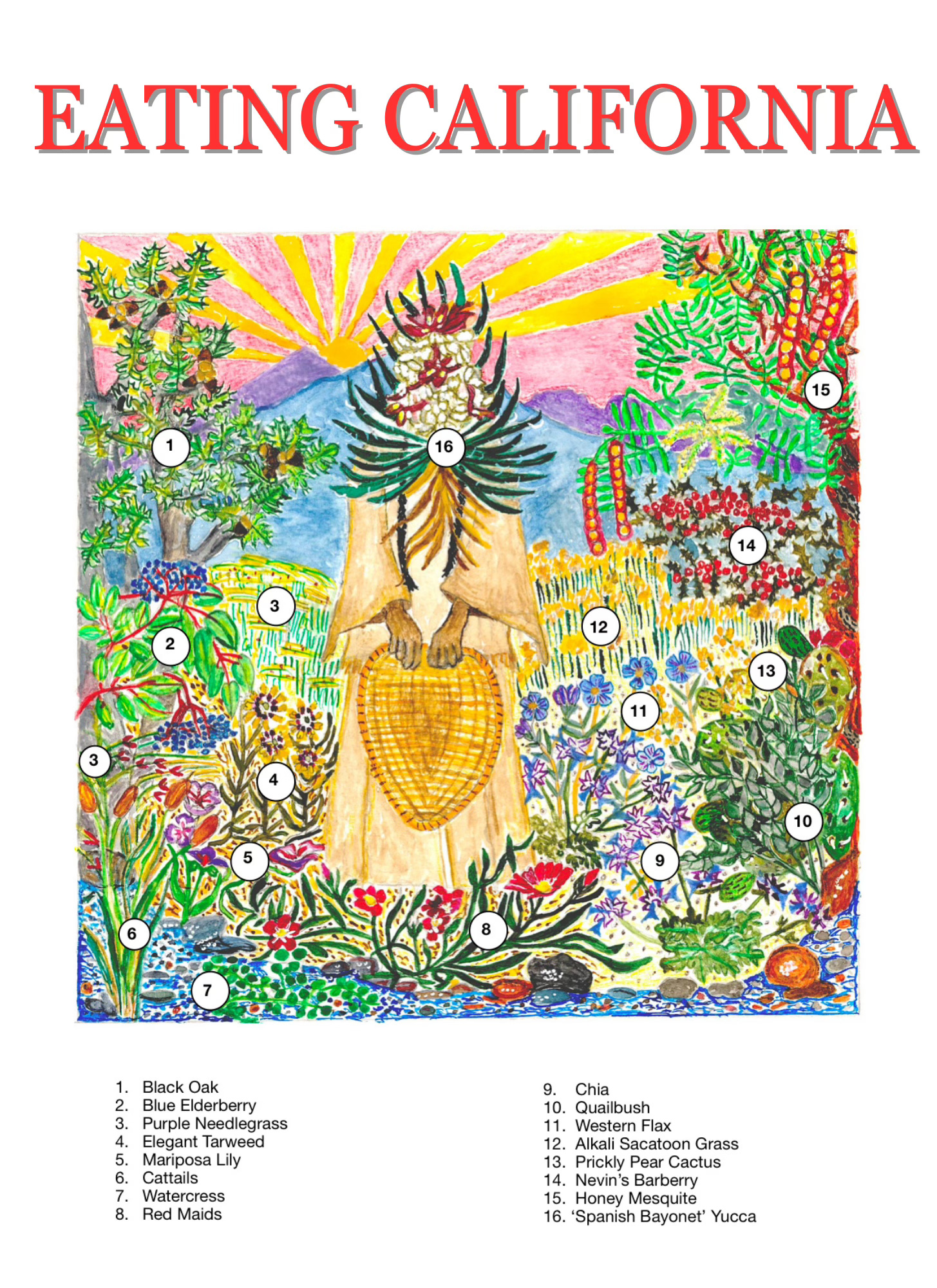

At first glance, Eating California is a vibrant, captivating artwork. But spend a moment with it, and you’ll find it’s more than just a feast for the eyes—it’s a story, a celebration, and a call to action. Created by artist and ecological visionary Alrie Middlebrook, this piece brings together 16 native California plants—all edible—to reconnect us with the land and the legacy of those who have stewarded it for over 20,000 years.

Honoring Indigenous Knowledge Through Art

The center of the work features an Indigenous woman holding a winnowing basket—a gesture both symbolic and historic. Traditionally used by Indigenous women for separating seeds from chaff, the winnowing basket is a powerful representation of food sovereignty, seed saving, and resilience.

“I wanted to represent the full geography of California,” Alrie explains, “so I placed Northern California on the left, and Southern California on the right. And it was essential to center Indigenous women—not just as caretakers of culture, but as holders of ecological wisdom and power.”

The figure holds space with intention. She’s framed by Yucca schidigera—a plant chosen not just for its stunning edible flower mass, but for its deep-rooted significance. In Southern California’s Anza-Borrego Desert, archeological sites dating back 1,300 years reveal roasting pits and grinding stones used to prepare agave and yucca, a tradition that speaks to the enduring relationship between people and place.

Plants With Purpose

Each of the 16 plants in Eating California was chosen for its edible, ecological, and cultural value. From superfoods like watercress to traditional staples like mesquite and acorns, Alrie’s plant selections showcase the biodiversity and brilliance of California’s native food systems.

Watercress: Ranked among the most nutrient-dense foods, this aquatic supergreen grows well in hydroponic systems and represents what’s possible when traditional plants meet modern cultivation.

Mariposa Lily: Its edible bulb is rich in nutrition and potential—imagine commercially growing native bulbs as a sustainable food source. We could develop recipes to integrate their flavors into mainstream dishes.

Madi Elegans & Red Maids: These wildflowers produce seeds that were integral to traditional “power bars,” often bound with acorn fat and eaten on the move. Rich in protein and healthy fats, they’re an ancient answer to modern energy snacks. This combination of wildflower seeds was called pinole.

Chia: Well known today, chia seeds were prized for their water-retaining qualities. Tribes like the Tarahumara in Mexico have long used chia to hydrate and fuel long-distance runs.

Black Oak Acorns: Acorns were foundational to the Indigenous diet. Without them, studies show early populations faced nutritional deficiencies. Black oaks yield the preferred acorns for flour-making or gruel, a food that required immense labor and knowledge to process.

Clarkia, Elderberry, and Nevin’s Barberry: While some of these, like elderberry, have become popular again for their medicinal qualities, others like Nevin’s barberry are now endangered—making their inclusion a reminder of what’s at stake and what we stand to lose. Even though it’s endangered, Nevin’s Barberry thrives in native gardens.

Prickly Pear Cactus (Nopal): Edible in both its paddle and fruit, this plant offers low-glycemic nutrition and thrives in arid regions—perfect for adapting to California’s drought-prone future.

Honey Mesquite: Nitrogen-fixing and drought-tolerant, mesquite pods were ground into flour and used to make pancakes on hot stones—a sweet, nutritious staple in desert regions.

Purple Needlegrass: Though not traditionally eaten by humans, this native bunchgrass fed countless grazing animals. Its inclusion nods to the broader food web and the importance of preserving California’s unique grasslands.

Ecological Restoration Through Food

Eating California isn’t just a tribute to the past—it’s a vision for the future. Alrie urges us to recognize that these plants are not just artifacts; they are solutions. “Some of these plants can go five months without water. They’re resilient, they’re nutritious, and they belong here.”

Imagine growing native foods not just to feed ourselves, but to restore the land. Imagine creating modern snacks based on ancient knowledge—nutrient-rich, climate-smart, and deeply rooted in place.

A Call to Remember—and Reimagine

This artwork is aptly named. Eating California is an invitation to remember the flavors, the traditions, and the systems of care that have sustained people on this land for millennia. It challenges us to rethink what we eat, how we grow it, and who we honor in the process.

“I could talk for three hours about each plant,” Alrie laughs. “There’s so much history in every one of them.”

And through this living portrait of plant wisdom and Indigenous resilience, we are invited to listen, learn, and take part in restoring a more just and delicious California.